Blog |

|

2/23/2023 4 Comments Poet's Petard, March 2023Clearing the SpaceComposing a poem is probably much like taking trumpet lessons: you want to begin with a noise that demands a listening attention. A noise that clears space in advance for the poem, but is not yet the poem. Like the opening of the Early English epic 'Beowulf,' which begins with the single word “Hwaet,” that Seamus Heaney translates as “So.” Followed by a period, not an exclamation point. It could also be left untranslated and simply pronounced, which might give you more like its true purpose: to announce the upcoming delivery of a long story. No poem exists in a vacuum, like automatic writing that just pours out of you without any obvious preparation. For a poem to be “heard,” it's meant to incorporate at least a couple of familiar clues, which can remain largely untranslated. Where are we? Who is speaking? What's happening? The actual beginning of a poem can seem like “merely voice” no meaning like clearing the throat, a sneeze, the sharp intake of breath that follows the conductor's downward-plunging hand. In any case, the opening of any poem often involves a little purifying noise that needs to appear in some way on the page, and which is meant to be “answered” by a certain kind of silence. This little nursery rhyme always comes to mind for me when I feel a poem coming on. It works well as a way to “smudge the space” before you commit anything to writing.

There, now, the threshold is swept, you can haul out your various notes-to-self, your juicy fragments and see if you can find a core essence that will coalesce into a poem. Here's an example of a sure-fire “poem situation” that turned out to be impossible (for me, at least) to budge from its stolid, relentlessly-informational, self. Years later it remains in my notebook, unwept, unhonored and unsung.

Rae Armantrout has somehow allowed the all-too-ready pronoun “It,” to linger in the poetry ante-room long enough to send out several tantalizing hints of precocious metaphorical prowess.

And there is William Carlos Williams' poem that, without the opening four words might have been just a list, or a poem fragment that went reeling out before it had waited for the proper space to be cleared.

4 Comments

1/23/2023 2 Comments POET'S PETARD FOR JANUARY 2023In Which Rain Identifies Itself By Sound Not SongWe seem to be in rainy season once more. Rain as a season, not yet a climate. We are bewildered to recognize again the variety of voices It (Rain) has commandeered for Its personal use – and we might be excused for confusing “song” with “noise” at this very fundamental level, instead of the clearing of new space between sound and light. Here are a few samples of ways that poets are hearing rain. First, Thomas Merton, out of his forest solitude: (from 'Rain and the Rhinoceros'): “The rain I am in is not like the rain of cities. It fills the woods with an immense and confused sound. . . .What a thing it is to sit absolutely alone, in the forest, at night, cherished by this wonderful, unintelligible, perfectly innocent speech, the most comforting speech in the world, the talk that rain makes by itself all over the ridges. . .everywhere in the hollows! In eight two-line stanzas Donna Henderson winkles out a set of “only rain could do this” sounds. The poem ends only when she, like the rain, takes a deep breath. (from 'Much Raining' in her collection Send Word):

Here is Jorie Graham reaching into the silence when the rain does actually stop: (from 'All' in the London Review of Books, 8/30/2018):

Finally, a segment of my poem 'Rainproof' describing how the rain sounds in my study when it comes off the roof and slides its way through a jury-rigged arrangement of connecting gutter-pipes, distracting my attention just enough to allow me to mis-hear almost its entire journey as a protective covering for a song that could emerge no other way:

11/27/2022 0 Comments Poet's Petard for November, 2022Green Halloween As I look out my window today (October 22) my view is blocked by a Japanese Maple so covered with green leaves I can't even see the street. Farther out in the yard my aging Curly Willow, showing no sign of recognizing the austere requirements of seasonal shift, has spent the summer deftly thickening its allotment of green way past the top edge of my window. Together these trees seem quite prepared to take a stand of some sort. This is the climate of thunder storms, not blizzards, they insist. Throw away your orange and black, your pumpkins, your ghastly and skeletal frame of mind. It's too EARLY. The sun is still out. Well, all right. With the help of two poets, let us offer a final discreet (?) huzzah! to this year's GREEN: as climate, as weather, as biology, as geology, as joy as soul medicine, as cure. . . . First, representing the Spanish poets' total ownership of green in all its aspects, this refrain from Federico García Lorca's The Gypsy Ballads

Verde que te quiero verde. Just recite that while you're fending off grief or even something smaller, like a house in the middle of a river. Poet Laurel Chen recently encountered “wild grief” in her poem Greensickness (Poem-a-Day, October 21, 2022) one of those poems where the poet attempts to write her own version of going through unbearable grief and having no clue how to deal with it. So, she tries honesty, and what emerges is truly stunning. She finds herself in a field on her hands and knees, as if beaten down and waiting for her fate: All around me, the field was growing. I grew out Even as the poem progresses through a set of somewhat conventional tropes against grief, she has taken this “usual response” seriously, done her emotional homework, so to speak. Thus she is not caught by her own rhetoric, but rather re-purifies it in the emotional cauldron of her deepest self. Grief is not the only geography I know. She saves herself by the strength of her love of green, which has been building inside her all her life. Oh, I've loved so immensely. By the time she reaches this stage in her relationship with grief and green, she has gone way past

reciting a prayer of supplication and rather is reciting a prayer of gratitude. 10/16/2022 1 Comment Poet's Petard – October, 2022Sunlight So often, when I speak about the sun, an enormous red rose entangles itself in my tongue. But I do not have the capacity to remain silent. --Odysseus Elitis (my translation) Poets are accused of always writing about two subjects: love and death. This is true. But we also write all the time about light and dark. These dualities are not quite the same, but they operate like two monsters guarding the temple of Poetry. All poets must first make peace with them before we can truly turn our attention to all the other aspects of this demanding art I'd like to focus here on a few poets who have found a way to get past sunlight and live to make good poetry from the experience. British poet U.A. Fanthorpe offers her “translation” of the Christian story of creation, from the Old English poem “Caedmon's Song.” I'll give you the first 4 stanzas of 12. The poem is in her book Queueing For The Sun.

Nepal poet Durga Lal Shrestha at age 64 paid his respect to light by way of his poetry collection The Blossoms of Sixty-Four Sunsets (translated by David Hargreaves). Each two-stanza poem is part of a large dialogue between poet and sun. Here is poem #62: Rebirth

Finally, Vincent van Gogh, whose letters to his brother were saturated with color and light:

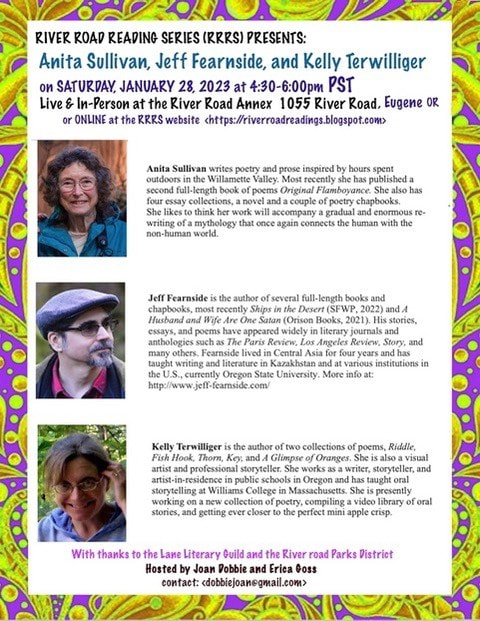

So there is every moment something that moves one intensely. A link to my new book: Original Flamboyance

7/11/2022 4 Comments Comfort FoodPoet's Petard for July 2022 Poetry is mostly known for its ability to excite, amuse and comfort. Right now, caught in a knot of history, with more than the average gut-punching controversies drawing down our emotional reserves, I would imagine people who normally never touch the stuff (poetry, I mean) are turning to poetry out of desperation. Yet, sometimes poetry's response to the agonizing cry “Is there Balm in Gilead?” is a resounding “Nope!” and the frown and kick to go with it. People are finding it unusually hard to develop into sane, compassionate, clear, humble and steadfast adults. How can we best make use of poetry to help us out? I'd like to offer you a few quotations from my personal trove of “words that comfort me even if I don't know exactly why.” This first one is a little nerdy, but every time I read it. . . .well, you'll see:

Here are the opening lines of a poem by Wang Wei (701-761) translated by Florence Ayscough and Amy Lowell:

Here are three from my own collection of poetry orphans. I call “parentheses” because the only thing they share is a kind of incipient randomness, like a collection of tips of icebergs*

*Footnote: Some poets have made up their own name for those groupings of words that don't quite get to 'hold down' a formal category. Mine has been “parentheses,” but others might be “studies,” “dispatches,”“monologues,” “perambulations,” “doors,” “liminals,” “short takes,” “centuries,” “conjugations.” Many poets make up their own forms as a kind of temporary generating discipline, Certain persona poems also serve this need – to act as poetic “trellises” that offer support to ideas that would likely never emerge in any other way.

6/5/2022 2 Comments Poetry Keeps Its SecretsThink about Poetry as a raw material – a bar of pure metal which is physically pulled or “drawn” through increasingly narrow die openings until it becomes wire fine enough to vibrate at a musical frequency. Normal daily speech does not easily tolerate the level of stress required for this kind of precision. Poetry uses the same words as prose narrative, but because the majority of its work in the world deals with processing the most extreme human emotions, a poem goes through a great deal of pressure as it is being drawn, and may occasionally kick up into a kind of spontaneous descant, beyond control by the rational mind, and lasting just long enough to bring about a new relationship in the world that was previously absent. Poetry is partly a language unto itself, hmmm yes. . . .but which language? Poems can be translated from one human speech to another, but what were Poetry's own very first words? There are hints. Listen to this from Monica Gagliano, a plant-communication specialist who is one of an increasing number of scientists who have “gone over” to Poetry in order to find the vocabulary & metaphors they need to continue accurately documenting their work. (From her book Thus Spoke the Plant):

Here linguist and translator George Steiner in his book After Babel, is complimenting Shakespeare for intuitively understanding that individual words truly do not have definition outside of the full context of whatever surrounding words they are temporarily thrown into contact with.

In her book Nay, Rather, translator Anne Carson mentions a word in Homer's Odyssey even the poet himself did not translate any further than to bring it across with only its ancient Greek pronunciation to guard it from becoming revealed. Although the single-syllable word seems to refer to a plant that is probably a nightshade, Carson makes no attempt to draw a correlation with a real plant, since, as she says,

There is a sense building here, not only of plants as conscious beings with their own method of communication, but also that words themselves can be said to dwell in their own world, sharing much with us, but not everything. I ran across this same idea in a fantasy novel by Oregon-born (and recently deceased) author Patricia A. McKillip. She's referring to the long and arduous years of memorizing and translating that the ancient Irish bards went through: (from The Bards of Bone Plain)

So, words have their own world; plants have their own secret language, and Poetry is the closest we humans ever get to either. What a challenge! What a joy! I'll close with a rare example of a poem where the poet is so addled by his original image that he steps aside almost in bewilderment, and allows the process to take its own course, rather than trying to describe his way out of his overwhelmed state. Brodkey manages to open a space for Poetry to come in like an interior decorator, to select and juxtapose some words which, in a normal, rational sequence might sound like just one damned thing after another.

--Harold Brodkey 4/30/2022 4 Comments Poetry as AphorismLet's touch lightly upon the poem as aphorism. Most poets don't deliberately write aphorisms and call them poems, probably because aphorisms are innately stodgy: they flaunt rather than hide their didactic role of summing things up, so that you can't read too many of them in a row without cleansing your palate between doses. Hint: the aphorism too often can sneak into the last stanza as a way of validating and “clarifying” the good intentions of the poem. However, the (often hidden) aphoristic tendencies of poetry can be fun to mess around with as a kind of literary device. I would even go so far as to say a well-placed aphorism can completely change the “body chemistry” of the entire poem, even if in itself it seems innocent of any such intention. Here are a few one-liners from Greek poet Yannis Ritsos (died, 1990), ably translated by Paul Merchant in his book Monochords. Ritsos regarded them as daily warm-up exercises.

Ritsos was possibly writing one-liners in the tradition of Heraclitus (c. 500 BC) whose tendency was more majestic (tr. by Brooks Haxton in Fragments: the Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus):

A contemporary poet, and there may be many others, who very deftly uses an aphoristic approach (think: summing everything up in the last line) is Lawrence Raab. Here's the final 1 ½ stanzas of his poem “Lost” (Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, Fall 2017)

And here's the stunning final line of one of my favorite poems by Jorie Graham, 'Subjectivity' – a long poem that labored mightily and brought forth a yellow butterfly!

To finish, here's a poem of mine in which I deliberately succumb to the tangled logic that can be the death of a good aphorism.

– Martin Prechtel (The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic) Much soul-searching is taking place in these historically difficult times, some of it private, but some through the enormous and complicated sieve of the collective unconscious. We feel one another's pain, so much so that once again we find ourselves re-visiting the perennial “Problem of Humans,” and once again hoping for the possibility to see it in a new light. The light of Poetry, for example, especially its ability to stimulate visionary thinking. Poetry is vastly under-rated, under-utilized and misunderstood in the world we have mostly inhabited as rude guests for some 250,000 years. Our inconsiderate behavior has sometimes been so gauche and ignorant that I wonder if that in itself is part of a Larger Plan yet invisible to us. Does the Earth benefit from humans wreaking havoc upon its stately code of reciprocities? In many origin myths, humans make their entrance rather late, and deeply unfit for the lives they have been destined to lead here. As if our entire world had been built upon an error – which should be logically impossible. At various times we are said to have been made of: mud, sticks, wood, cloth, and sometimes even then had to be forgiven many times in order to remain on the shelf at all. But even though the creator god destroys each flawed version of our species when inevitably it proves to be inferior, and starts over with a different set of ingredients, the story does not allow any realistic effort to root out and avoid the endless repetition of the mistake. As if the origin myth itself is the problem – a tossed-off first draft, truly little more than a bare outline, unable to include matters like quality of material, integrity of design, or anything at all about ways to improve our initial conditions. Some ancient origin myths, especially in the East, insist that the chief work of the Universe and everything in it, is to become fully conscious or enlightened. Furthermore, that we humans have actually been very slowly, but collectively working ourselves into a fully awakened state, far beyond simple awareness. If this is true, however, it surely seems that we should have been fully conscious for quite some time already. If the vast and powerful universe so urgently needed us in order to manifest this one trait it could not bring into fruition itself, why has it spent so much energy and still not met its goal? I know I must be asking the wrong question all over again. Were humans side-tracked by words?Did someone empty a huge tin of alphabet letters onto the path we were so imperfectly following, and suddenly, as they began to blow away, we disappeared into the woods on either side, snuffling like wild boars, having at last found our true calling? There in the bush we discovered-were-discovered-by – Poetry! Poetry uses words in different proportions and densities than does prose. It is essentially a sixth sense, a separate way of being alive that for some reason was handed over to humans. We have an exclusive contract to preside over the eons of its unfolding. Perhaps the Universe is in thrall to our final “aha!” when we make that one last connection and become conscious. I like to think we human beings carry inside us – like a sort of Original Virtue – a capacity for the raw metaphor that underlies everything. And in a strange mathematics of twos and threes, metaphor is primary. We can only truly understand anything at all through analogy to something we already know. It is the final and the first, the breakaway, the Form that emerges of its own accord out of tendency, out of strange attractiveness, out of whim. Yet most people never experience poetry as metaphor at all, even though it is hourly revealed in the gaps of meaning that naturally occur between poetry and prose. Our odd deafness to this achingly simple state of affairs, has prevented us for a very long time from returning to the full capacity for consciousness each one of us is capable of. (and yes, I did end a sentence with a preposition, hoping that might be a small step in the right direction. . . .).

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed